Like other aspects of human nature, it can be sublimated or driven underground for a time-but only for a time. Countries putting their own interests first is the way of the world, an inexpugnable part of human nature. Not only is there no superseding authority, no world government, above the nation-state to enforce transnational morality there is also no higher law for nations than the law of nature and no higher object than self-preservation and perpetuation.įor all its bluntness and simplicity, America First is, at its root, just a restatement of this truth. In this sense, Thomas Hobbes is instructive: All countries live in the state of nature vis-à-vis one another. That said, one never sees nations sacrificing themselves for other nations, the way individuals sometimes do-by fighting for their country, for example. Yet many countries do so because their leaders have concluded that welcoming the dispossessed serves some higher good. For instance, it’s rarely in a country’s direct interest, narrowly construed, to accept refugees. Indeed, states sometimes do things that run counter to their immediate interests. After all, what else is the purpose of any country’s foreign policy except to put its own interests, the interests of its citizens, first?įew countries ever act exclusively out of self-interest. But the phrase itself is almost tautologically unobjectionable. The other, more familiar phrase for the president’s foreign policy-“America First”-is much maligned, mostly for historical reasons. He was encouraging countries already on this path to continue down it and exhorting others not yet there to pursue it. He was also forthrightly saying that this trend was positive. In both cases, the president was not simply noting what was going on: a resurgence of patriotic or nationalist sentiment in nearly every corner of the world but especially in parts of Europe and the United States. General Assembly, he made the same point by referring to a “great reawakening of nations.” In perhaps his most overlooked, understudied speech-delivered at the APEC CEO Summit in Da Nang, Vietnam, in November 2017-he encapsulated his approach to foreign policy with a quote from The Wizard of Oz: “There’s no place like home.” Two months earlier, speaking to the U.N.

(To see for yourself, try describing the Monroe, Truman, or Reagan Doctrine with just a couple of words.) Yet Trump himself has explained it, on multiple occasions. The problem is that the Trump Doctrine, like most presidential doctrines, cannot be summed up in two words.

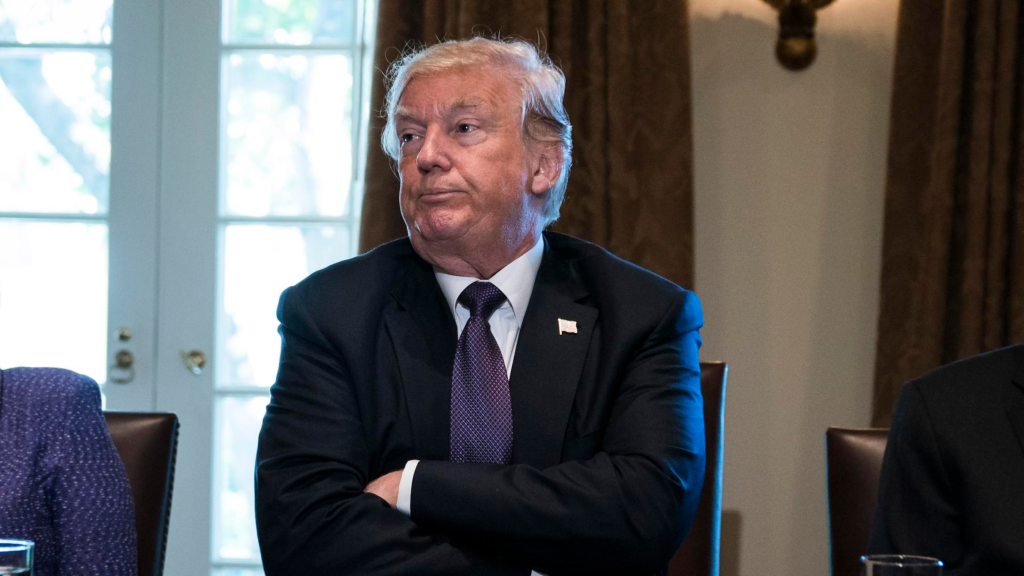

The administration calls it “principled realism,” which isn’t bad-although the term hasn’t caught on. Yet Trump does have a consistent foreign policy: a Trump Doctrine. His foreign policy doesn’t easily fit into any of these categories, though it draws from all of them. The same goes for the fact that he has no inborn inclination to isolationism or interventionism, and he is not simply a dove or a hawk. So the fact that Trump is not a neoconservative or a paleoconservative, neither a traditional realist nor a liberal internationalist, has caused endless confusion. This article is derived from a lecture he delivered to the Program in Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University. National Security Council as deputy assistant to the president for strategic communications. From February 2017 to April 2018, he served on the U.S. Michael Anton is a lecturer and research fellow at Hillsdale College. People treat names as sacrosanct categories and can’t process things not yet named. foreign-policy establishment-current and former officials, international relations professors, think tankers, and columnists-uses names as a crutch.

The underlying phenomenon is what matters the name is just shorthand. But to dredge up an old philosophic argument: The name is not the thing. Names can be useful in sorting and cataloguing ideas and in avoiding the unnecessary elaboration of things everyone already knows. Whatever one thinks of his tweets, however, the fact is that he has also delivered a number of speeches that lay bare the roots, contours, and details of his approach to the world.Ī simpler-and more accurate-explanation for the confusion is that Trump’s foreign policy does not yet have a widely accepted name. Many critics blame this confusion on the president’s purported inarticulateness. President Donald Trump’s tenure, there is still endemic confusion about what, exactly, his foreign policy is.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)